Managing priority habitat species-rich grassland

Shoot owners who manage grassland habitats can apply for annual funding of up to £646 per hectare from Defra.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Apply for funding for your project or make a donation today

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

Dr Cat McNicol challenges perceptions of the Birds of Conservation Concern list and explains why interpreting it in isolation has negative implications for shooting.

The IUCN red list is a system that highlights the extinction risk of species. It includes animals like the Critically Endangered northern hairy-nosed wombat and the Near-Threatened emperor penguin.

The list acts as a global triage system for species conservation. Interestingly, the idea for a bird conservation list originated from Sir Peter Scott, a well-known wildfowler, artist and founder of WWT.

The triage method has been adopted by various organisations to prioritise species of interest. In the UK, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) created the Birds of Conservation Concern (BoCC) List in 1996 for this very purpose.

The list has been updated four times since – we are now on BoCC5 – and uses a traffic light system to allocate birds into three categories: Red, Amber and Green. In a period where we are experiencing widespread species declines, the BoCC list is an important tool for highlighting which species should be conservation priorities. But it is all not quite as straightforward as that.

At first glance, the colour system seems simple to interpret. ‘Red’ is bad, ‘Amber’ suggests there are issues, and ‘Green’ means no problems. So, for some of quarry species, such as pink-footed geese, gadwall and woodpigeon which are amber-listed, one might assume it is time to renounce our guns and stop harvesting them.

In fact, a well-known vegetable box company’s founder recently made this assumption in their newsletter: “Like the once common starling and sparrow, [woodpigeon] numbers are now much depleted; in some areas, they are already regarded as endangered”. Such a simple interpretation of the traffic-light system is incorrect and, without the right context, can lead to misguided decision-making.

The BoCC list does not solely represent species population trends. The species assessment process it uses considers multiple criteria relating to both the wintering and breeding populations of each species.

If the species passes certain thresholds for ANY of these criteria, it is assigned to a list. Criteria include:

The final of one of the above criteria (‘international importance’) is applied to species where more than 20 per cent of the European population breeds or winters in the UK. For this reason, for many of our amber-listed quarry, an amber listing does not necessarily represent anything problematic.

For example, the amber-listed gadwall has a globally favourable population, showing widespread growth trends (70 per cent increase in the last 25 years) and, you guessed it, they are amber-listed because the UK hosts in excess of 20 per cent of the European population in winter.

Numbers of pink-footed geese are increasing across the board but the species is amber-listed because we host 85 percent of the global population over winter. The same story is mirrored for other quarry including greylags, shoveler and teal.

So, it is not always due to population declines that these species are amber-listed, in fact, the increasing population trends of many of these wintering species only cements their place in the amber category.

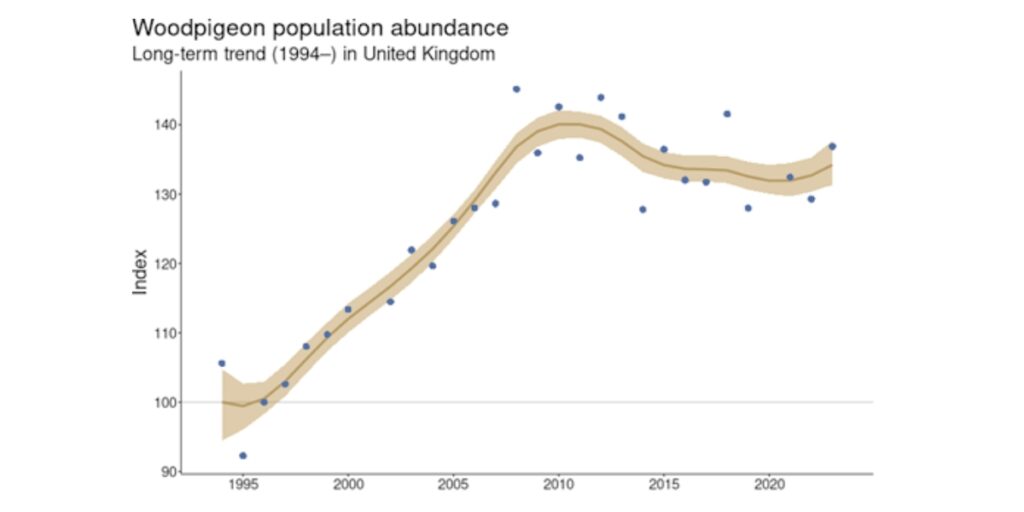

And it is not just our wildfowl that highlight such nuances in the colour-coded system. The abundant woodpigeon provides another example of an amber-list anomaly. With more 5.1 million breeding pairs in the UK, this widespread species’ population is at an all-time high. By sheer volume this means that it represents over 20 per cent of the European population. Again, therefore, it is amber-listed.

Without context, one would assume harvest of amber-listed quarry should be restricted, as, there are several amber-listed birds which are genuinely declining. Common starling, nightingales, dippers and kestrels, for example are all red or amber-listed due to breeding population declines.

A superficial understanding of the BoCC list can lead to unnecessary management and hunting decisions. We must remember that it is not always due to population declines that these species are amber-listed. In fact, increasing population trends of many of these wintering species only serve to cement their place in the amber category.

When we use the BoCC listing, its accompanying in-depth report and other data sources together, we can generate a hugely informative picture of our quarry species status in the UK, and how to best focus conservation and management efforts. Indeed, in an original BoCC report, authors highlight that the simple categorisation gives an indication of overall population status and when “taken together with other information, should inform the setting of conservation priorities.”

At BASC we believe harvest and conservation of our quarry should be sustainable and evidence-led. BoCC represents just one aspect of that evidence, which alone is too simplistic, and ultimately not designed for policy decisions. However, when used alongside a suite of other metrics and evidence bases, the BoCC categories can be informative.

Ultimately, it is a tool in the box rather than being one list to rule them all.

Shoot owners who manage grassland habitats can apply for annual funding of up to £646 per hectare from Defra.

BASC was one of four ‘Interested Parties’ defending against Wild Justice’s legal challenge to burning regulations in England.

BASC has criticised the current legal framework on protected sites that leaves shooting activities disproportionately restricted.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter and get all the latest updates straight to your inbox.

© 2025 British Association for Shooting and Conservation. Registered Office: Marford Mill, Rossett, Wrexham, LL12 0HL – Registered Society No: 28488R. BASC is a trading name of the British Association for Shooting and Conservation Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under firm reference number 311937.

BASC Direct Ltd is an Introducer Appointed Representative of Agria Pet Insurance Ltd who administer the insurance and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, Financial Services Register Number 496160. Agria Pet Insurance is registered and incorporated in England and Wales with registered number 04258783. Registered office: First Floor, Blue Leanie, Walton Street, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP21 7QW. Agria insurance policies are underwritten by Agria Försäkring.

If you have any questions or complaints about your BASC membership insurance cover, please email us. More information about resolving complaints can be found on the FCA website or on the EU ODR platform.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

More information about our Cookie Policy