Getting their ducks in a row

As wildfowling comes under increasing pressure from changes in lifestyle and consenting arrangements, the Leicestershire Wildfowlers Association is one of several forward-looking clubs pushing the boundaries.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Apply for funding for your project or make a donation today

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

We have previously looked at four areas where shooting can help get woodlands into good ecological condition. Now, we look at one of these, the degree of open canopy, and how to plan the year ahead to get it done.

The government’s National Forest Inventory assessments are very clear that most of the woodland across Great Britain is failing on one or more of the 15 criteria it looks at. One of the biggest issues is that our woodland canopies are too closed, starving the woodland floor of light for bluebells and violets to regenerate or for the development of a decent shrub layer.

Woodcock is one species that is suffering from lack of light levels, with science listing canopy closure and over-grazing by deer among possible reasons for the decline we have seen in native woodcock numbers and range. It is not just quarry species, of course. Creatures like woodland butterflies are also impacted when light levels are too low, as are nightingales and other woodland birds.

It’s almost certain that much of the woodland you have access to has this exact problem, but it can be hard to see because that is what ‘normal’ woodland looks like. The question is, what does ‘good’ look like? What should you be seeing?

If the woodland is less than 10 hectares then we should have 10 per cent of it as open space. If the woodland is larger than 10 hectares then it’s between 10 per cent and 25 per cent.

Now that probably feels like a lot, especially if you get towards the 25 per cent end – but remember it is across the whole area. The only key rule to remember is the canopy gap must be at least 15m wide to count. So, the rides we often cut for beating access under the canopy is not what we are after. These and other smaller open areas are valuable – think of a dark conifer plantation versus a light and airy ash or birch wood – so we need to create them as well.

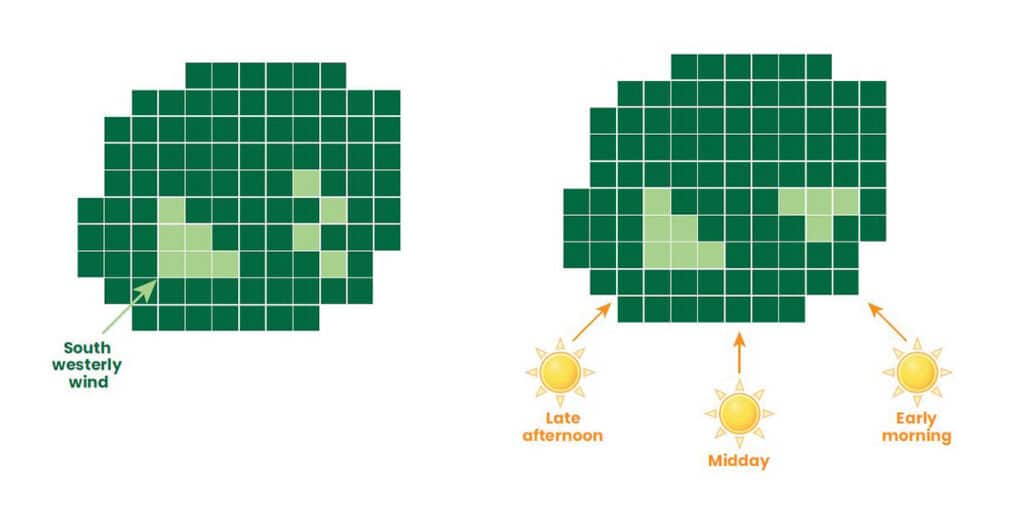

Look at the representation (top right) of a one-hectare woodland. Each of the cells represents a 10m2 block. As the woodland is less than 10ha we need to consider a 10 per cent canopy gap. In the top example, in the south west corner we have six blocks together forming a flushing point or glade for deer management. The gaps are wider than 15m, so these count. However, those 10m blocks on the south east are not counted towards our 10 per cent because they are less than 15m wide.

The diagram below shows I’ve replanned those south east blocks so that they are adjacent and in a T shape. So not only are they over 15m wide, but the T shape will create a channel for sunlight to get into the woodland floor more easily on the north side.

If you have woodlands over 10 hectares then you have a lot more to play with, 10-25 per cent, and for woodlands of that sort of scale you’ll probably have chances of multiple flushing points to allow you to drive it in sections or have flushing points that suit different wind directions.

And that brings us onto some other points to think about when planning canopy gaps; the wind, sun and topography of the land.

Strong wind can push trees over, so those trees on the outside of woodlands tend to invest more energy into creating stronger root systems and their canopy grows like a car spoiler so the wind slips over it. Be wary about felling these trees, as the trees they are sheltering will be more susceptible to windblow. We’ve probably all seen when a compartment of trees has been felled for forestry and the newly exposed trees have subsequently been blown down. So bear this in mind where you create open spaces.

The sun is also a big factor when planning open spaces. Early and late sunshine is low in the sky and so the south side of the woodland is going to shade the north. If you want your open spaces to provide warmth for game and wildlife (which you do!) then think about creating a shape that lets that low sun into woodland itself, hence the T shape in the lower representation.

The final thing is topography. For example, woodlands on north-facing slopes are hidden from the light of low sun and, especially in winter, some parts may barely get direct sunlight at all. Consider the shapes you can create with your topography that minimise windthrow risk but maximise the chance of sun penetrating.

The late autumn and winter months are the core times for felling operations. It avoids the bird nesting season and if you are cutting with the intention of the tree surviving to regrow, like coppicing or pollarding, it’s the kindest time, as the trees are relatively dormant. So, there is a small window left in the new year to do some felling work before the sap rises and early breeding attempts start. If that is too soon, then now is the time to plan for autumn work.

Clearly, you will need permission from the landowner, and possibly others with an interest in the woodland. Is there a forester for example? What is the long-term purpose for the woodland? Is it for nature conservation only, or is there an intention to harvest timber from it? Your aspirations for good shooting need to be considered in tandem with these other purposes.

The other thing you need is to consider is felling licences. If you are cutting below five cubic metres of wood per calendar quarter, and not selling more than two cubic metres of it, then you are under the threshold for needing a licence. The allowance covers the main trunks and major branches. Depending upon how much you need to do and how fast you want to do it, you may be able to operate under this exception and create your open space levels over a year or two, especially in smaller woodlands.

Above these limits then you need to apply for a felling licence, which will likely require a forest management plan. This will be worth it in the longer term and may open opportunities for public funding through the forestry schemes.

Health and safety runs all the way through this. If you have the skills and qualifications to carry out felling, that’s fine. If not, then get someone who has to do this for you.

Odds-on where you shoot there is a lot of woodland needing to be opened up. You don’t have to eat the elephant all at once. You could move several woodlands towards favourable condition over a few years. By all means go faster but make sure you get advice. You can call your local BASC regional or country team to talk through your aspirations and plans from a shooting and conservation perspective. When you need that professional forester advice, then we encourage you to get it. Last month we mentioned the PIES project which provides free advice in England. It is well worth considering a call to them for further on-site advice. Otherwise, your Forestry Service has staff available to advise landowners on their options to extend and improve the condition of woodland. Don’t be in the dark. Let there be light.

As wildfowling comes under increasing pressure from changes in lifestyle and consenting arrangements, the Leicestershire Wildfowlers Association is one of several forward-looking clubs pushing the boundaries.

BASC joined the Deputy First Minister, Huw Irranca-Davies, on a national park visit to to see how targeted conservation measures are helping curlew in Wales.

A study carried out by BASC and the University of Exeter into the UK’s resident woodcock population has heralded positive results.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter and get all the latest updates straight to your inbox.

© 2025 British Association for Shooting and Conservation. Registered Office: Marford Mill, Rossett, Wrexham, LL12 0HL – Registered Society No: 28488R. BASC is a trading name of the British Association for Shooting and Conservation Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under firm reference number 311937.

BASC Direct Ltd is an Introducer Appointed Representative of Agria Pet Insurance Ltd who administer the insurance and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, Financial Services Register Number 496160. Agria Pet Insurance is registered and incorporated in England and Wales with registered number 04258783. Registered office: First Floor, Blue Leanie, Walton Street, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP21 7QW. Agria insurance policies are underwritten by Agria Försäkring.

If you have any questions or complaints about your BASC membership insurance cover, please email us. More information about resolving complaints can be found on the FCA website or on the EU ODR platform.