Capercaillie: Highland rescue

The Scottish capercaillie risks extinction but a recovery plan supported by the BASC Wildlife Fund, is already making progress.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Apply for funding for your project or make a donation today

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

Project Penelope is here again giving us the opportunity to get cracking once more with this exciting international conservation scheme, the chairman of the Preston and District Wildfowling Association Chris Kelly.

On our marsh, the wigeon flight in as dusk deepens, feed all night, and then leave in the morning to roost on the river. We are fortunate to have good stocks of the species throughout the winter. Our involvement in Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) counts often show the wigeon population to range from 5,000 to over 7,000. So, when the opportunity to get involved with Waterfowlers’ Network’ Project Penelope arose, we jumped at it. We are passionate about the conservation of the wildfowl that frequent our estuary, and keen to broaden our knowledge of where these wigeon go. This should help us improve our understanding of what can we do as part of an international effort to ensure that wigeon thrive and survive for the future. Knowledge is the key.

Preston and District Wildfowlers Association (PDWA) were involved in the WAGBI mallard ringing scheme almost half a century ago. Project Penelope is an opportunity to learn about and be a part of something bigger. It is a chance to show what wildfowlers are all about; a chance to meet with others who are also passionate about wildlife but not from a hunting background; and a chance to meet and engage with others, talk with them, and break down misconceptions on all sides.

Catching wigeon with cannon nets was very alien to us at first. There was a lot of preparation required in getting the birds into the catch area, then a stealthy approach needed to reach the hide, which was 200 metres from the net. We’d watch as the light slowly improved, checking the safety zones, and be frustrated by birds sitting on top of the net, which prevented us from firing. Alas, success in the early days was limited – often we’d run out of time as the morning wore on and the wigeon would leave to roost on the river.

Eventually we decided it was time to try something different, so we switched to dusk outings instead. Our success rate improved…

The atmosphere in the hide was electric as we watched bunches of wigeon up to 20 strong flighting into the carefully re-fed site. With the aid of a thermal imaging unit, we could see the numbers building on the catch area. There was a real sense of excitement as Louise counted down: “Three… Two… One… Fire!”…

Our aim was to catch 100 birds; the final count came to 102. To minimise the chance of disturbance, the rest of the team – the ringers, measurers, weighers, and recorders – had been sitting in their vehicles half a mile away, waiting to hear the boom of the net that would be their signal to get going.

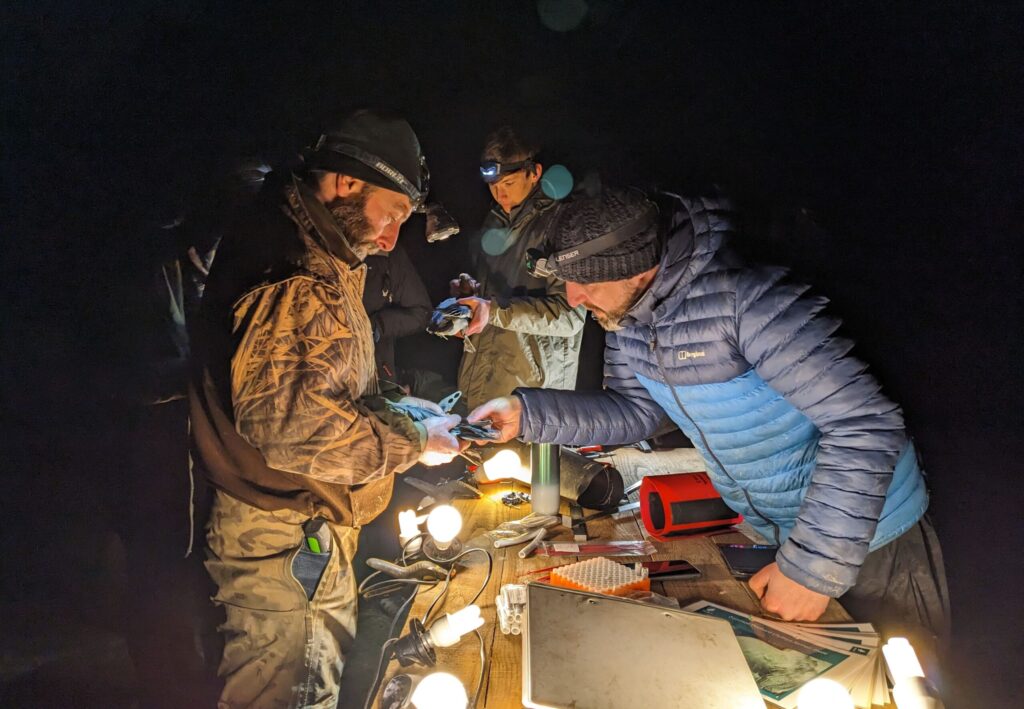

It amazes me how calm the birds are under the net. The first job was to transfer the birds into disinfected poultry crates and separate the species. Ten to twenty birds per crate, depending on size, seems to keep them calm. As it was fully dark by the time we had reached this stage, the crates were placed away from the lights of the table where each bird was weighed and measured.

It didn’t take long to get into an assembly line for ringing and recording the birds. Most of us were strangers to each other, but the team worked seamlessly together.

It is quite rewarding to us as wildfowlers to be breaking down the barriers of each other’s misconceptions. It was a great evening – everyone there was a volunteer and some had travelled considerable distances to be a part of this collaborative exercise. Ninety-nine birds rung and processed, three escapees when getting them into the crates; isn’t it grand when a plan comes together?

We now have great hope for future catches. As wildfowlers, we are privileged to be able to host such an event, and look forward with fingers crossed to more success with Project Penelope as part of our larger conservation strategy.

Project Penelope was launched during the winter of 2021 and brings together ringers, wildfowlers and scientists with an interest in Eurasian wigeon. The project, led by the Waterfowlers’ Network, links teams working in Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Britain, and Ireland to build upon previous work and improve knowledge of annual migrations, site fidelity and survival. Rings and (in some cases) GPS tags have been funded by the Wildlife Habitat Charitable Trust (WHCT), The Danish Hunters’ Fund for Nature and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland.

In Britain, over 40 ringers, from the Highlands of Scotland to Kent in the south, are contributing to the study. To date, over 900 wigeon have been colour-marked in Britain alone and re-sightings of these birds have been received not only in Britain but the Netherlands, Belarus and Russia.

The numbers of ducks being ringed today are on the decline and, with changes to our wintering duck populations, it is now more important than ever to be collecting data to help inform the drivers of these population declines.

Why are fewer ducks being ringed today? Firstly, there are fewer ducks wintering in Britain and Ireland than there once was; the so-called ‘short stopping’ phenomenon now sees birds wintering further east than they once did. Secondly, duck ‘decoys’ – large, netted, funnel-like traps, once used to bring food to the table, and more recently used to capture birds for ringing – have now mostly fallen into disrepair or are long gone. Ringing activities led by the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust have also been scaled back, due to re-prioritising of work areas.

These days, on average around 2,000 ducks are ringed annually, compared to 7,000 in the 1980s. Given the reduced duck ringing effort, we must explore new ways to increase annual ringing totals to also include biometric data collection, while being mindful of additional threats posed, such as avian influenza.

In America, the ‘duck banding’ effort is championed by wildfowlers who actively catch, ring and release several thousand ducks each year.

Such banding projects are seen as long-standing cooperative research projects between wildfowl biologists, managers of wildfowl populations and wildfowlers themselves.

In return, a considerable amount of information is garnered, allowing a more detailed understanding of wildfowl populations, hunter behaviour, age and sex classes, species-specific survival, and crippling loss. All of these parameters help to ensure the harvest is sustainable.

Wildfowlers have access to sites frequented by duck species and they can help with site access, reconnaissance and the feeding of sites prior to catching. These opportunities and collaborations could be a way of increasing future duck ringing activities and should be thought about in future duck ringing programmes.

Wildfowlers have access to sites frequented by duck species and they can help with site access, reconnaissance and the feeding of sites prior to catching. These opportunities and collaborations could be a way of increasing future duck ringing activities and should be thought about in future duck ringing programmes.

Kane Brides is a senior researcher at the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust.

The Scottish capercaillie risks extinction but a recovery plan supported by the BASC Wildlife Fund, is already making progress.

In honour of World Wetlands Day, we discuss some of the wetlands projects supports by BASC and the BASC Wildlife Fund.

It’s all change at Lindisfarne this season with a new warden but there are several ways you can experience wildfowling there.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter and get all the latest updates straight to your inbox.

© 2025 British Association for Shooting and Conservation. Registered Office: Marford Mill, Rossett, Wrexham, LL12 0HL – Registered Society No: 28488R. BASC is a trading name of the British Association for Shooting and Conservation Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under firm reference number 311937.

BASC Direct Ltd is an Introducer Appointed Representative of Agria Pet Insurance Ltd who administer the insurance and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, Financial Services Register Number 496160. Agria Pet Insurance is registered and incorporated in England and Wales with registered number 04258783. Registered office: First Floor, Blue Leanie, Walton Street, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP21 7QW. Agria insurance policies are underwritten by Agria Försäkring.

If you have any questions or complaints about your BASC membership insurance cover, please email us. More information about resolving complaints can be found on the FCA website or on the EU ODR platform.