50 not out

Sparsholt’s history stretches back 125 years. Fifty years ago, the college pioneered the country’s first dedicated gamekeeping course.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Apply for funding for your project or make a donation today

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

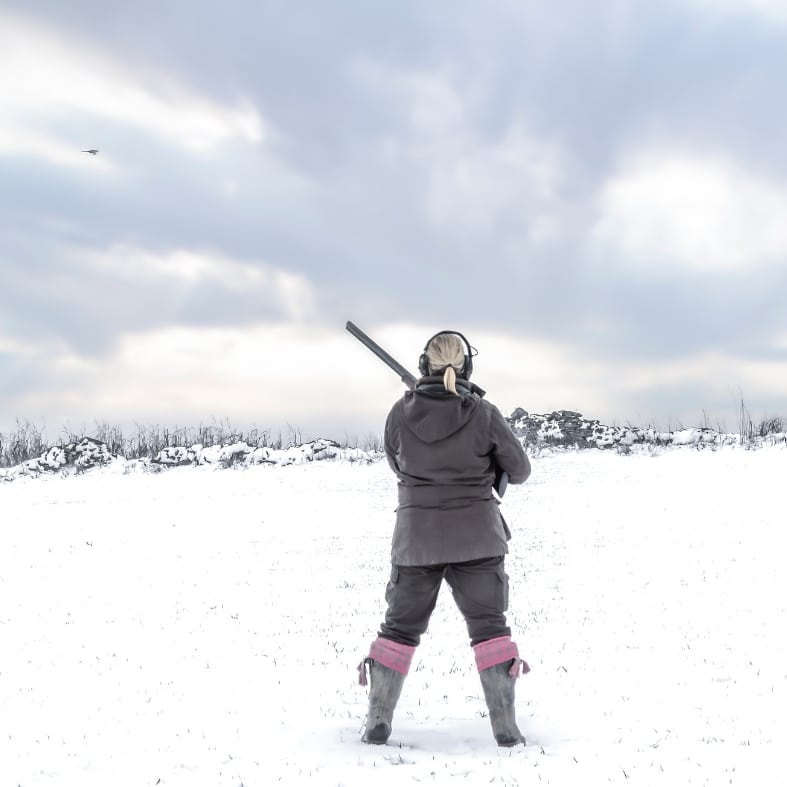

Pheasants in the last month of the season can provide the most testing and enjoyable shooting, as Roderick Emery knows only too well.

Time was when ‘cocks only’ was the rule after Christmas. Actually after Boxing Day, because Boxing Day was a full-on family event where all bets were off. Except safety rules, of course. Boxing Day was for the young and was a very special treat indeed, eagerly anticipated by the youthful tyros who would finally be getting their chance on the peg.

Less enthusiastically welcomed, perhaps, by some of the older Guns who might have overindulged in the, hem-hem, spirits of Christmas, which you might have thought age and experience would have taught them to give a bit of a swerve. But then age and experience are wasted on some people, especially where exotic post prandial digestifs are concerned.

However, in the crisp dawn of a new year it was always cocks only. This was because keepers would be setting about catching up the hen birds as laying stock before the season finishes. While you need plenty of hens to generate the young who will provide the sport in the following season, you only need a handful of cocks to keep them company. And too many cocks left among the wild stock will spend so much time parading about and fighting each other instead of getting in among the ladies, that they may never get around to getting the business done before the mood passes.

So, there is much to be said for shooting cocks only.

After the grand battues earlier in the season, the shoots of January were set aside for less prestigious teams. The tenant farmers would get a go. And the resident agent might be given a day. Then the keepers take a day where they can return the many favours that accumulate among the countryside networks that keep the whole thing ticking over year after year. The beaters’ day was – and remains – the reason many of us turn out week by week to thrash our way through the undergrowth for the benefit and pleasure of others; not the only reason, obviously, but standing on a peg where you have watched any number of illustrious guests humbled over the season is always a moment to savour.

I cut my shooting teeth on January days and it is not merely the glow of recollection that puts them among some of the best; there are sound reasons why January pheasants are not just good, but better.

Shooting well-presented pheasants is never easy, but shooting cocks only adds another level of skill to the whole undertaking.

Picking off a brace of cocks from a flush of birds takes concentration and precision – especially if the sun is behind the birds as they appear. The jeopardy now may only be a modest fine for a worthy cause and a good deal of leg pulling over lunch but, back in the day, dropping a hen bird by mistake was a serious issue. Just leaving birds didn’t get you off the hook either. The point of cock shooting is to shoot cocks, and failing to take your chances could see your name crossed off the invitation list just as easily as putting a potential laying bird in the larder.

There is a strong argument, too, for saying the birds are just better in January. They are that little bit older, of course, and perhaps fitter and stronger as the result; and they’ve been over the Guns a few times into the bargain. I’m not sure pheasants learn from their experiences any more than some of us learn from ours, but anyone who has not heard tell of wily January cocks sliding out the side door the moment the beaters’ wagon draws up at the top end of Jubilee Copse has not been listening enough, I reckon.

The reason for their flightiness may be only logical. By mid-January the trees are bare of leaf and much of the bramble and undergrowth in the coverts has died back. In the chill of a frosty late-season morning with a bit of wind, even the crackle of frost underfoot will carry on the breeze and any chatter from the beaters will be heard the full length of a wood and beyond. Every pheasant with a sense of self-preservation will leg it for the boundary before the first spaniel gets even a whiff of its presence.

So, the Guns must be quickly and quietly onto their pegs and the stops have to be in position before the first tree is tapped. Everyone has to work that little bit better if the wily cocks are to be brought to book and to bag. And the birds do tend to be unpredictable. They may have flown obediently over the Guns in the early part of the season; and they may have flown higher and harder as the weeks progressed, but by January they seem to have found another gear altogether.

Perhaps it is because they see the Guns a little sooner through the sparse branches, or perhaps it is that the Guns see the birds a little earlier. Either way, any experienced pheasant shot will tell you that watching a pheasant curling towards you in open sky for too long does not increase the chances of connecting. The advice used to be: “Consider the line; then stand up, settle the dog, undo your jacket, check your watch – and then address the bird!”

Flank Guns especially may find they are given special instructions. “Your peg is on the apex but if they start to break out, then move up by all means!” And walking Guns can be in for tremendous sport on the outside of a long wood with the beaters.

If you are in the happy position of being on familiar ground and in the company of beaters whom you have known for many a season, then – if you shoot well – you might enjoy a very special experience. The cheers from the line as you fell twisting, spiralling cocks curling back on the wind again and again will take you to a place few Guns are lucky enough to visit.

If you miss everything that comes out, however, you will find yourself in a very different place. Both will linger long in the memory.

Even in the line of Guns in front of the birds you can find yourself having to reach a little further and swing a little faster.

Keepers looking to get on top of the cocks – and perhaps to make a decent bag for their January guests – are inclined to stretch the line to ensure more ground is covered and fewer birds are able to pass by out of shot.

So, while you might be only 30 paces or so from your next Gun in the run-up to Christmas, you can easily be double that in January. A bird that passes precisely between you – well up and with a bit of a curl on it – is within range for either Gun, but it probably presents a longer shot than many of us are used to. I am inclined always to use a little more choke and a somewhat heavier load after Christmas, therefore, to make sure I can reach out far enough for these birds with confidence.

And we should be confident. After all, this is not our first rodeo. We may not all be able to start our season in mid-August at the grouse and then shoot two or three days a week until we arrive in mid-January as a finely honed machine, but there is no doubt that practice makes, if not perfect, then at least better.

Flank, walking, back Gun, pegged out or double-banked, the January cocks always seem to be just a tad faster, slightly further away and seldom quite as straightforward as we might expect a pheasant to be.

And these are all, in my opinion, good things. Things to be savoured.

Nor let us forget those last-minute, last-day marauds with a handful of friends and a motley pack of dogs. We used to go hedging and ditching after the cocks in the waning hours of the season.

One on each side of the hedge – or ditch – and the rest spread out on the far side of the copse, with a distinct bias toward the downwind edge. There might be a cock or two to be rousted out from somewhere. Or a couple of mallard on the pond in the wood or, perhaps, a spring of teal. A woodcock could still be startled from its reverie. Or some pigeons clattered from the oaks as we passed. And no one shot a hare until we were close to home. At least no one with an ounce of sense did.

Aye, them were days!

Roderick Emery lives in East Anglia and has spent a lifetime in pursuit of game.

Sparsholt’s history stretches back 125 years. Fifty years ago, the college pioneered the country’s first dedicated gamekeeping course.

BASC Scotland is appealing to shoots to respond to a survey assessing the impact of Storm Arwen on their businesses.

As another game shooting season ends, we are going to say goodbye to our shoot friends and colleagues, but hopefully not for long.