Crossbows

Information on the definition of a crossbow, legislation around sale and hire of crossbows plus possession by those under the age of 18.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Apply for funding for your project or make a donation today

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

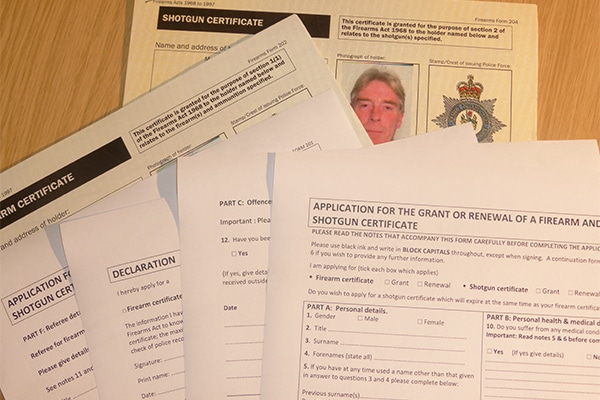

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

Home » Firearms » Firearms use » Additional conditions on firearm certificates

Section 27(2) of the 1968 Firearms Act states;

“This clearly infers that additional conditions should be the exception rather than the rule.”

Conditions, other than the statutory conditions prescribed by the 1998 Firearms Rules, are a mechanism for the chief constable to regulate the behaviour of a certificate holder where necessary, on a case-by-case basis. The original 1969 Home Office guidance on parliament’s intentions within the 1968 Firearms Act shows this.

Section 10.35 of the Home Office guidance 2013 says: “Section 27(2) of the 1968 Act gives the chief officer of police powers to attach conditions to firearm certificates where necessary.”

“Public safety” must not be extended to include restrictions on the shooting of certain legal quarry species. Public safety relates to the holder’s competence to take a safe shot when using a firearm over land. This assessment is dealt with at initial grant and via land checks. For example: stopping a certificate holder shooting a fox with a rifle held for deer has nothing to do with public safety. A backstop is always required.

It is ultra vires for police to impose conditions preventing a certificate holder from carrying out an operation that would otherwise be lawful. Police have an enforcement role with regard to the law, not to role to invent or embellish it.

10.37 of the guidance further says: “Every effort must be made to limit the number of additional conditions imposed on a firearm certificate and ensure that they are not contradictory. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that all ‘good reasons’ for which a firearm is possessed are allowed for, for instance stalking and target shooting.”

Conditions are not linked to ‘good reason’, nor do they automatically flow from it.

Conditions form no part of the process for determining whether the applicant has satisfied good reason. A certificate may be granted once good reason is met with or without conditions. Once good reason has been satisfied, then an appraisal may be made to see whether it is appropriate for any conditions to be imposed.

Home Office guidance para 10.38 says: “There is no requirement to establish good reason for additional conditions or the addition of quarry species to an existing condition where good reason. already exists for the possession of a firearm in the first instance (See chapter 13). Firearms should be conditioned to provide flexibility with quarry shooting by allowing all lawful quarry (see Appendix 3).”

Once good reason has been demonstrated for the initial possession of a firearm, additional conditions should be applied to allow other lawful uses.

13.16 Good reason to possess particular firearms will generally be linked to the quarry species found on the land concerned, for example on a farm or estate. However, conditions for the possession of such firearms should allow the certificate holder to deal with reasonable eventualities, for example pest or game species or the humane destruction of injured animals on the estate.

13.24 Chief officers of police will wish to be mindful that quarry species are mobile, and applicants may not be able to always predict their presence on land on a consistent basis. Certificate conditions should therefore allow the applicant flexibility in dealing with quarry species and the ‘any other lawful quarry’ condition may be used.

Note: In a letter to police licensing staff from the Home Office titled “reasonableness” and dated 9th December 2002 (ref: TDD-0372) it says;

“Guidance says that allowance should be made for ‘reasonable eventuality’ of game being present on the land (see paragraph 13.14). Whilst this appears to sometimes be contrary to the table in Chapter 13, it should be remembered that the table is there to establish the ‘good reason’ for the possession of the gun in the first place and should not necessarily be used to impose overly restrictive conditions.”

Secondly, the guidance was intended to deal mainly with the ‘good reason’ to acquire weapons rather than their use as such. We would certainly not wish to force shooters to acquire more guns than they need or to leave guns unattended because they are obliged to carry a selection.

Paragraph 10.33 of “Firearms Law Guidance to the Police” states:

“As the courts have held (R v Cambridge Crown Court ex parte Buckland, 1998) that there is no right of appeal against the imposition of conditions (as opposed to a refusal to grant or renew a certificate) chief officers will wish to be cautious in imposing conditions that might amount to a constructive refusal to grant or renew a certificate, that is additional conditions that would make possession or use so difficult as to be redundant in practice.”

10.36 says:

“Possible conditions, which may be applied are listed at Appendix 3 as a guide to firearms licensing officers. They should only be used, where the individual circumstances require it for public safety.

Exceptionally, chief officers of police may impose other conditions appropriate to individual circumstances. As the courts have held (‘R v Cambridge Crown Court ex parte Buckland, 1998’) that there is no right of appeal against the imposition of conditions (as opposed to a refusal to grant or renew a certificate) chief officers will wish to be cautious in imposing conditions that might amount to a constructive refusal to grant or renew a certificate, that is, additional conditions that would make possession or use so difficult as to be redundant in practice. There is a right of appeal against a decision to vary existing conditions in section 29, but not against the initial decision to impose conditions.”

The lack of an appeal procedure for a certificate holder aggrieved by a condition makes it incumbent upon chief constables to be reasonable in imposing conditions. Conditions must be competent in law and ‘Wednesbury reasonable’.

In his judgement on the Buckland case, His Honour Judge J Haworth said: “That upon a grant the Chief Constable shall specify any conditions, subject to the test of Wednesbury reasonableness.”

Wednesbury unreasonableness is a standard used in assessing applications for judicial reviews of decisions by public authorities under English law. It applies to a decision, which is “So outrageous in its defiance of logic or accepted moral standards that no sensible person who had applied his mind to the question to be decided could have arrived at it.” [Lord Diplock in Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service (the GCHQ case 1983)]. Whether a decision falls within this category is a question that judges should be well equipped to answer. It is possible for a decision to fail a proportionality test without being Wednesbury unreasonable.

In the words of Lord Greene [Associated Provincial Picture Houses v. Wednesbury Corporation 1947]:

“It is true that discretion must be exercised reasonably. Now what does that mean? Lawyers familiar with the phraseology used in relation to exercise of statutory discretions often use the word ‘unreasonable’ in a rather comprehensive sense. It has frequently been used and is frequently used as a general description of the things that must not be done. For instance, a person entrusted with a discretion must, so to speak, direct himself properly in law. He must call his own attention to the matters, which he is bound to consider. He must exclude from his considerations matters, which are irrelevant to what he has to consider. If he does not obey those rules, he may truly be said, and often is said, to be acting ‘unreasonably’. Similarly, there may be something so absurd that no sensible person could ever dream that it lay within the powers of the authority.

A typical example of unreasonableness that relates to firearms licensing is when conditions are applied to make a lawful activity unlawful, for example, to impose a condition restricting a person to shooting “foxes while deer stalking”.

The “foxes whilst deer stalking” condition prohibits night shooting as deer can only be legally shot during daylight hours. The condition also prohibits a rifle being used on land where the deer have moved away, albeit temporarily or where there are no deer in the first instance.

Such a condition only seeks to force the holder to obtain another rifle which the police feel is appropriate for unrestricted fox control and to make secondary trips after stalking has ceased. Aside to night shooting, to make separate visits is often incompatible as foxes are active at the same time as deer at dawn and dusk.

In essence, an applicant is either safe to have a rifle or not, if he or she needs a specific calibre by law for deer stalking and the application is approved for the person to shoot the largest quarry species in the UK, then shooting a fox with the same rifle will also be safe, humane and legal.

The process of taking a safe and humane shot is identical across the species and must of course includes a safe backstop. The aspect that police are looking to be satisfied about is the competency of the applicant to take a safe shot every time. The shooting of any quarry requires a safe backstop for the shot, and the process/experience is translatable between quarry species.

In addition to an applicant’s ability to take a safe shot, police also allege that larger calibres capable of humanely shooting the largest species of deer are ‘unsuitable’ or ‘overkill’ for smaller species such as fox.

The primary concern for police is whether there are issues around an application due to lack of energy to achieve a humane kill, not to attempt to measure excess energy which will be absorbed by the backstop.

When it necessary to impose conditions, they must have the following attributes:

These can be broken down as follows:

Lawful

Note: A condition which is incompetent in law does not bind the certificate holder.

Unambiguous

Written in plain English

Reasonable

Proportionate

Non-contradictory

Demonstrably beneficial to public safety

Properly notified

Evidenced

Where conditions need to be employed, they should be evidenced and the evidence should be:

Negotiation

When there is disagreement with the wording of conditions, such conditions must be negotiable. Where a request is made for a condition to be changed, the burden should fall upon the police to justify its retention, rather than vice versa.

Please listen to the concerns of your customers and be prepared to justify and document your actions. If you fail to do this you leave yourself open to complaint and possible public censure.

End note

The right to impose conditions places considerable power in the hands of firearms licensing staff. At a stroke you can make that which is otherwise lawful, unlawful. It is ultra vires for you to impose conditions preventing a certificate holder from carrying out an operation that would otherwise be lawful.

BASC recommends that licensing staff always ask themselves what the benefits and disadvantages of imposing a particular condition may be. For preference, unless the individual circumstances clearly justify them, conditions should be avoided. If conditions are used the evidence for applying conditions should be documented.

If additional conditions must be used, please use them sparingly and wisely, and with a clear and evidenced record of their benefit to the public safety.

Got a question? Email us on firearms@basc.org.uk or call 01244 573 010.

© BASC July 2023

Information on the definition of a crossbow, legislation around sale and hire of crossbows plus possession by those under the age of 18.

This page has been created to help provide you with the latest guidance on travelling abroad with your firearms.

Firearms licensing is in crisis right now, so what can you do to give yourself the best chance of getting your renewal approved sooner rather than later?