Trapping pest birds in the UK

Pest and predator control is an integral part of conservation and wildlife management and it is necessary to reduce predation and damage to acceptable levels.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Apply for funding for your project or make a donation today

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

Home » Pest and Predator Control » Mink control guidance

The non-native American mink (Neovison vison) has become widely established throughout the UK since the 1950s following escapes and releases from mink farms. Mink have had a devastating impact on our native fauna through predation on vulnerable species of birds, fish (especially stocked waters) and mammals such as the water vole (Arvicola amphibius).

The decline in water vole numbers can be directly attributed to predation by mink, which generally live and hunt near water, and can swim well. The female mink pose the greater threat since they are small enough to penetrate the water voles’ burrows, thereby overcoming the voles’ last line of defence.

Conservation bodies accept that mink control is an essential tool in water vole conservation. However, this control must be appropriately targeted, humane, and form part of a wider strategy to include habitat management for the water vole.

This guidance is intended to help you control mink in the most effective and least labour-intensive way possible. We recommend that you read the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust’s Mink Raft Guidance Note and the Water Vole Conservation Handbook which this guide complements.

We would also like to stress the importance of recording your mink control activities.

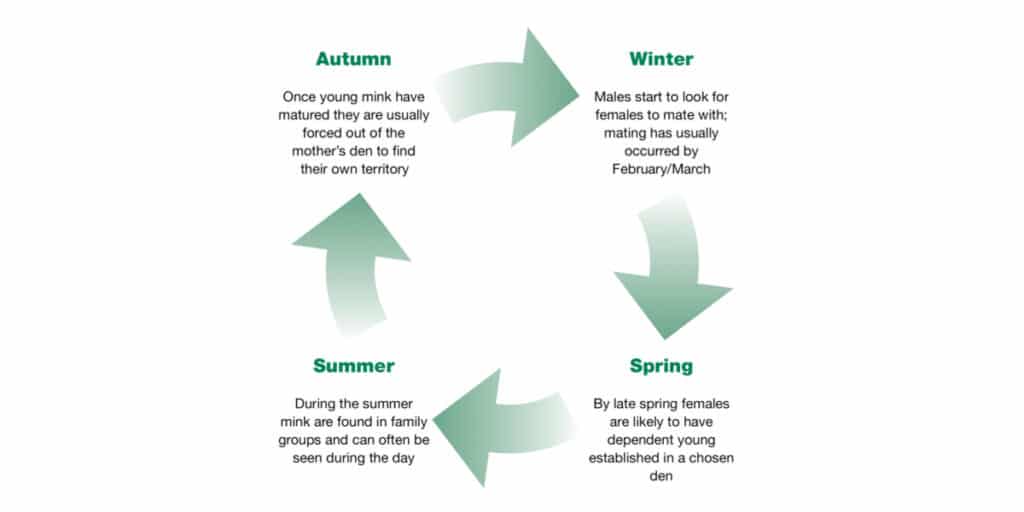

It is useful to know the biology and habits of mink so that you can take steps to control them effectively and humanely. The diagram below gives an overview of the mink’s lifecycle.

Mink are opportunistic carnivores. They will feed on a variety of prey including birds (waterfowl and ground nesting farmland birds) and mammals (water voles, rabbits etc). They are curious creatures and will often investigate tunnels, burrows and man-made objects, although there is evidence to show they avoid close proximity with humans.

Mink will mark their territory with distinctive scats in the same way that otters leave spraints. Scats and footprints at a site can often be a good way of establishing whether mink are present.

Female mink have a single litter each year, typically between April and early May, of between 3-6 kits. While nursing the young, she will hunt intensively over her home range (approx. 3km of waterways), and this can have a devastating impact on water voles and nesting birds within the area.

Therefore, the removal of female mink close to water vole colonies before the end of April will protect those voles and birds during their breeding season.

Trapping is a legally acceptable and most effective way of controlling mink. Live capture using a cage trap, followed by shooting, is considered the most appropriate method because it avoids the risk of harming non-target species. It is easy, humane and efficient and allows non-target species, such as water vole, to be released.

Although homemade designs can be effective, purpose-built live-capture cage traps are preferable. BASC recommends the use of the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust’s (GWCT) mink raft (where there is suitable water to deploy it), complete with a live-capture trap. In order to minimise the chance of capturing otters, the trap opening should be small enough to exclude them or be restricted by adding an otter guard.

Set rafts and traps where mink are most likely to encounter them. Particular features to look for include confluences of watercourses, inlets or outlets for ponds and lakes, where drains, hedges or fence lines meet watercourses. Islands and purpose-made mink rafts are also key places to locate traps.

It is advisable not to position rafts or traps in the open, particularly beside public footpaths.

This is in part to avoid theft, vandalism and distress to trapped animals. If it is not possible to site rafts and traps out of sight, consider a notice on the raft or trap to inform people that it is a legal trap and should not be tampered with.

It has been shown mink control is most effective when the rafts/trap positions are at 1km intervals on a watercourse. This requires many people to make an effective network, so a co-ordinated programme of mink control is essential for best results.

If putting rafts on watercourses, it is also important to make sure that the appropriate public body is aware of the project as some types of raft design need to be registered with them. If you are part of an organised mink control project please check with your co-ordinator.

Trap between January and mid-April to minimise the potential breeding population of mink and from August to December to catch dispersing and wintering animals.

The advice from the National Water Vole Steering Group is that mink trapping should not be undertaken when female mink may have dependent young (between mid-April and the end of July).

Do not set traps in extreme weather – torrential rain or storms – as this can cause undue distress or death of captured animals (which may not always be mink). Once monitoring and the necessary trapping have started it should be kept up.

Mink will continually re-colonise unoccupied areas if they are not being controlled on adjacent land.

The Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust mink raft was developed as a means of detecting mink and as a good platform for trapping.

It is a floating raft that can be used in either monitoring mode, which uses a wetted clay pad to record footprints and monitor the presence of mink (and other animals), or trapping mode once signs of mink have been detected. A trap placed on the raft will generally catch mink within a few days if it has left its tracks during the monitoring stage.

Once the raft has been positioned in a suitable location and attached securely to the bank, install the clay pad and secure the cover. Cover the top of the raft with some vegetation to make it less conspicuous.

The raft should be left to accumulate evidence for between one and two weeks before a visit is made to check for prints.

We have included examples of commonly encountered field signs, prints and clay pad impressions which will help you establish which species are using your raft.

If you are uncertain, take a good photo of the impression or faeces with something to help scale the image (a coin for example) and send it to your co-ordinator or local expert.

If you find signs of mink, you can then convert the raft to trapping mode.

Once signs of mink have been identified, the mink raft can be converted into trapping mode using a live-capture trap.

Setting the trap

Once the trap is set, take care to ensure the cover fits properly so that the animal is sheltered and the trap mechanism works correctly.

In some situations, the trap with food (cat food or fish heads for example), or mink pheromone increases the chance of trapping mink.

Checking the trap

Once set, the trap should be checked at least once every 24 hours. The best time to check a trap is in the morning as many riverside animals are most active during the night.

Removing animals in the morning reduces the chance of their discovery by the public and their exposure to light and heat during the day. If the trap cannot be checked at least once every 24 hours it should be removed or pegged open.

Non-target, protected species (e.g. otter, water vole) must be released when you inspect the trap. If your trap contains a mink, the animal must be killed as it is illegal to release it back into the wild.

That is also a legal requirement for trapping grey squirrels.

Rats can be killed or released at your discretion.

It is recommended that an airgun, rather than a firearm or shotgun, is used to dispatch any mink caught.

The mink must be kept still in the trap to allow for an accurate humane dispatch shot. This can be done easily by using two plywood combs to push the animal firmly against the side or roof of the cage, restraining it in the manner of a livestock handling crush.

The mink may squeal when exposed from under the tunnel or restrained, so it is advisable to prepare the airgun, pellets and comb(s) before removing the tunnel from the raft. However, do not load the gun until the animal has been restrained; release the safety catch only when you are ready to fire the shot.

Using the combs as a lever, push the mink up to the roof or side of the trap and with the gun barrel perpendicular to the skull, shoot the mink.

Hold the gun’s muzzle a few centimetres away from the head and try to avoid the centreline of the skull as it is very strong.

A single shot should be enough to kill the mink, however, if a second shot is required take it as quickly and safely as possible, aiming at the junction of the skull and neck to destroy the brain stem.

Once death is confirmed the airgun should be unloaded and made safe.

Death is confirmed by:

Once the mink has been dispatched it should be:

Keeping a record of where your rafts or traps are and what success you have had is essential for both your own knowledge and for the assessment of any mink control network you are part of.

We have produced a mink control recording form which captures the key information.

Filling this out each time you move a trap, detect signs of water voles or mink, and when you trap mink, is vital because you will not remember the details later.

It is important to share this information with any project you are working on if your efforts are to have the best value for wildlife conservation. It will enable that project to analyse your results and observations and provide feedback to you and others taking part.

Completing the form as you go is the most important thing. However, you can save your co-ordinator a lot of time if you have been given an electronic copy by filling it out online.

Then there is no issue of legibility and it lessens the time needed to input your information to a central database.

Pest and predator control is an integral part of conservation and wildlife management and it is necessary to reduce predation and damage to acceptable levels.

We run a wide range of courses, covering all areas of shooting, including an introduction to woodpigeon shooting.

Find out everything you need to know below. Whether you are new to pest control, or want more practical advice we’ve got you covered.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter and get all the latest updates straight to your inbox.

© 2025 British Association for Shooting and Conservation. Registered Office: Marford Mill, Rossett, Wrexham, LL12 0HL – Registered Society No: 28488R. BASC is a trading name of the British Association for Shooting and Conservation Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under firm reference number 311937.

BASC Direct Ltd is an Introducer Appointed Representative of Agria Pet Insurance Ltd who administer the insurance and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, Financial Services Register Number 496160. Agria Pet Insurance is registered and incorporated in England and Wales with registered number 04258783. Registered office: First Floor, Blue Leanie, Walton Street, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP21 7QW. Agria insurance policies are underwritten by Agria Försäkring.

If you have any questions or complaints about your BASC membership insurance cover, please email us. More information about resolving complaints can be found on the FCA website or on the EU ODR platform.